SOMETIMES THE PERSONAL ISN’T POLITICAL

How data made me a revolutionary

I’ve been going to church occasionally, with a friend of mine and her granddaughter. I wasn’t raised in the church and I am not a believer, but I am beginning to understand the value of gathering with some of your neighbors once a week, reflecting together and singing some songs.

It’s too bad, I now realize, that this version of church is so muddied up with all those other versions of church: the one where the church is a platform from which to manipulate great swathes of people into voting against their own interests, for example; or the one where the church is used as a battering ram against women and LBTQ people; or the one where the church turns out to be a massive pedophilic child abuse ring.

From the pew of my little church in New Orleans, I see the version of church that people love so dearly. I can see that it’s possible for the same idea to be at once a force for good in our private personal worlds, and a force for evil in our shared political world.

Some of our personal convictions work a lot better if they remain personal. When we try to make them political (i.e., attempt to apply them to society as a whole), they don’t achieve what we hoped and intuited they would, and sometimes they even hurt, instead of helping.

I think many of my liberal readers already embrace this idea, when it comes to Christian Republican convictions (”one man, one woman!”, “it’s a child, not a choice!”, “thoughts and prayers!”). But strap in, Lib Dems, cus I’ve got a piece for you, too.

THE ABORTION RATE DOESN’T CARE ABOUT YOUR FEELINGS

To further illustrate the concept, let’s talk about abortion.

If you really hate abortion, and you’ve never read any data on the topic, I can see how you might think that making abortion illegal is a good way to drive down the abortion rate.

Alas, it has been tried a number of times, and the data has revealed that it is not. The real-world result of banning abortion is not fewer abortions, but more dangerous abortions.

So truly noble-hearted pro-lifers (I’ve met some!) should face the fact that abortion bans are not good legislation. They are supposed to result in fewer abortions, but they don’t. Instead, they kill a bunch of pregnant women (which, I hope we can agree, is pretty anti-life).

Similarly, “abstinence education” does not result in fewer teen pregnancies, “thoughts and prayers” does not result in fewer mass shootings, and “building a wall” will not result in more jobs or less crime.

All of these ideas are “political” only in that they are being used successfully to manipulate voters. None of them is (or can become) a successful policy, according to our hardworking and underappreciated friend, data.

For contrast, here’s some data that could be really useful in policy-making, if anyone bothered to read it:

- Countries with more restrictions on abortions tend to have higher abortion rates. When countries with legal abortion provide women with access to free birth control, on the other hand, the abortion rate plummets by AS MUCH AS SEVENTY-FIVE PERCENT.

- Legalizing sex work has been shown to decrease reported sexual assault and rape by THIRTY PERCENT OR MORE. Providing safe online venues for sex workers to find clients (the opposite of the recent SESTA and FOSTA bills) has been shown to REDUCE THE FEMALE HOMICIDE RATE BY 17%. (Read that again. It’s insane. Now read this. Or, if you don’t feel like reading, just listen to this podcast.)

- There are six times as many vacant houses in the US as there are homeless people, and it costs a ton of money to police the homeless population for nonviolent offenses. Why don’t we just give them houses?

Isn’t data cool?!???

This is why it’s a good idea to craft legislation and political strategies based on data, rather than on what feels intuitively or emotionally “right”. When we are unwilling to examine that distinction, we run the risk of 1) turning our adorable private beliefs (thoughts! prayers!) into ineffective, counterproductive, or dangerous political policy, and 2) ignoring data that can actually save lives, in favor of continuing to debate ideas that are politically pointless (eg: “is abortion right or wrong?”).

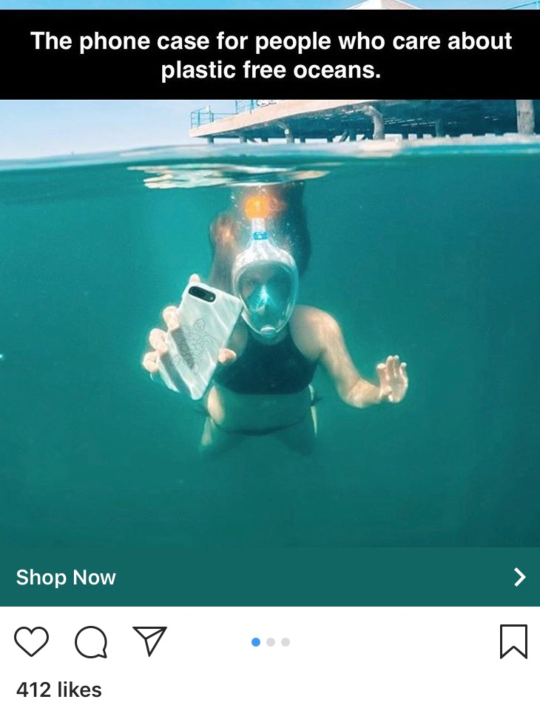

PLASTIC DOESN’T CARE ABOUT YOUR FEELINGS, EITHER

But guess what other ideas are personally adorable and politically pointless? “Don’t use straws”. Also “go vegan”, “buy organic”, “reduce, reuse, recycle”, and “impeach Trump”. Regardless of their intuitive or emotional impact, none of these ideas has a snowball’s chance in hell of addressing the problems they aim to address, and thus, as political strategies, they are more or less “thoughts and prayers”. Here’s why:

- Worldwide plastic production is projected to increase by 400% by 2050.

- Organic food still has a conspicuous lack of conclusive evidence for its benefits to health or the environment.

- Despite the fact that vegetarianism and veganism appear to be trending in the U.S. and Canada, global meat consumption is on the rise and is projected to continue rising steeply (76% by mid-century).

- That’s because the entire populations of the U.S. and Canada make up only 4.75% of the total world population (and dropping), with the world population expected to double by 2074.

(And, y’all, I hate to remind you, but impeaching Trump (almost certainly) gets us President Pence: an equally insane demagogue who is poised to enact possibly-even-more-terrifying policies.)

I’m not arguing that these ideas have no impact, or that they are bad ideas for you to apply to your personal life (e.g. if you have a Trumpian psychopath living in your household, you should certainly kick him out). I’m arguing that their impact on the problems they aim to solve is so immeasurably, impossibly small, that they will never get within a mile of the ballpark of solving them.

And that therefore, going vegan or eschewing plastic straws is in fact not a political act, but a personal one; like going to church, or getting a pedicure.

I’m not saying this to bum you out, or to judge you (I literally just got a pedicure). I’m saying it because when we pretend that “don’t use straws” is a political strategy, and will help us to address the life-threatening global crisis of ocean pollution, I think we are perpetuating a kind of confusion which could perhaps inhibit our ability to engage with these problems on the level of reality.

Which is, unfortunately, where most of us will have to continue living.

SCALE IS CONFUSING

The difference between political ideas and personal ideas is scale. The ocean, for example, is not a pool in your backyard (which you can simply refrain from filling with plastic). It’s a body of water which covers the entire planet, and is affected by all human activity. And “all human activity”, although it is made up of a bunch of individuals doing individual activities, cannot be accurately portrayed by the phrase “a bunch of individuals doing individual activities”. It’s better described in terms of human systems: institutions, governments, militaries, cities, countries, corporations and industries.

To approach these massive, complex, ocean-polluting systems as though they are a collection of individual people sipping beverages through straws is an ineffective tactic. So ineffective, it really can’t be called a tactic at all.

One way to determine whether something is a good tactic is to ask yourself: if this project was 100% effective, what would be the measurable result? Eg:

- If 100% of humans stop using straws: ocean pollution will decrease by up to .025%

- If 100% of humans switch to organic food: the environmental benefits will be mixed, and we will grow 25–34% less food.

That’s not to mention the fact that it is probably impossible to achieve a 100% effectiveness rate with ideas like these, because so far they are available to only a small subsection of people in a few very wealthy countries.

So, no matter how intuitively correct they may seem, at the scale of the entire globe (the scale where the oceans and the atmosphere exist), these ideas have roughly the same impact that “thoughts and prayers” have on mass shootings: they make a lot of people feel better about the fact that they are doing nothing to address a looming, life-threatening crisis.

If you ask me, we like to think that these ideas are politically effective for exactly that reason: because otherwise we will have to face the coming apocalypse of climate change, and the fact that humans on-the-whole are doing approximately jackshit about it.

And I understand why you’d want to avoid that! It’s fucking terrifying.

But my hunch is that we should instead admit that we’re doing jackshit about climate change, that the straws and the veganism and the potential impeachment were a waste of political energy, and that we are all absolutely terrified.

If we need to calm our nerves after that, we can go get pedicures.

And then perhaps, with a clearer head and calmer nerves, we can work on creating some actual political strategies.

YOU CAN’T CHANGE THE WORLD BY YOURSELF

Out here in terrifying reality, large-scale problems require large-scale solutions. And although it is intuitive to think that large-scale solutions are made up of lots of small-scale solutions (stop each person from using each straw!), it is sadly untrue. Complex systems – countries, economies, organisms – just don’t behave like a collection of small parts.

Similarly, major societal changes aren’t really made of a bunch of individual people making a bunch of individual changes. They are made of large-scale, long-term, coordinated applications of science, money, propaganda, and strategic organizing.

The right wing seems very clear on this fact, and uses it to great political effect (for example, we are still debating the “rightness” of abortion, despite its total irrelevance to policy-making, because they realized in the 1970s that debating abortion gets more people to vote Republican).

On the liberal left, though, I think there is some confusion about it. “The personal is political”, “think globally, act locally”, and “be the change you want to see in the world” get thrown around a little too frequently, and usually as advertisements for water bottles.

How quickly we forget that when Gandhi said “be the change” (which, by the way, he didn’t), he was probably referring to organizing millions of his countrymen in revolutionary acts of civil disobedience, towards a specific and well-defined political goal. He was not talking about buying a glass water bottle.

A relevant term to introduce here might be “phase transition”. A phase transition is when a system suddenly jumps from one phase to another. Boiling water is a good example: as you gradually turn up the heat on a pot of water, it just becomes gradually hotter water, until you get to 100C. Then, all at once, it becomes boiling water. And boiling water (in order to release the gas that the water is transitioning into) behaves very differently from hot water.

What we need to survive on this planet is not incrementally fewer straws and more Priora, it’s a global phase transition into an entirely different societal structure. And the individual consumer approach (“ask everyone to stop using plastic straws, then ask them to stop driving SUVs, then ask them to stop eating beef…”) is not just devastatingly slow, it is doomed to ineffectiveness.

It’s like trying to boil a pot of water by doling it out into Dixie cups and asking your friends to breathe hot air onto each individual cup. Intuitively, it seems like it might eventually work (the water is getting hotter, right?), but alas. No matter how good a job we each do with our little paper cups, the water will never boil.

If we want to boil the water, we need to pour all our cups into the same pot.

CANADA IS NOT THE WORLD

“But Canada is banning single-use plastic!”, you say. “Isn’t that a large-scale solution?”

Again, and unfortunately, it is not. Although “all the straws in Canada” is a lot more straws than “that one straw you’re using now”, it is still not even in the neighborhood of enough straws. The scale of plastic straw usage in Canada, when compared to the scale of plastic pollution in the oceans that span the planet earth, is just one more lukewarm Dixie cup.

The idea that Canada’s plastic ban is “a big win for the environment” only illustrates how resigned we are to losing. We are so resigned, we aren’t even capable of thinking about the problem at the appropriate scale.

If the Canadian single-use plastic ban has a 100% success rate, the oceans will continue to be 100% fucked by plastic.

That’s partly because there just aren’t that many Canadians. It’s also because consumer plastics are mostly not what ocean pollution is made out of (just like personal cars are mostly not what climate change is made out of).

And finally, it’s because everyone is not going to stop using plastic. Everyone is also not going to stop using petroleum-burning vehicles, or cows, or rice paddies. Everyone is not going to stop doing anything, unless and until the global industrial system allows us to do so.

We are still using petroleum not because we haven’t yet convinced each individual person to stop, but because the entire world economy is based on petroleum, and every powerful government on earth includes or is influenced by representatives of the petroleum industry. We are still using petroleum because the petroleum industry has its own lobbyists and politicians and spies and assassins and propagandists and governments.

We are still using petroleum because, at this point in history, the petroleum industry has a lot more influence over us than we do over it.

This may seem like bad news. But here’s the good news: we are not a bunch of individual people, facing a bunch of individual problems. We - the humans - have just one big problem. Our problem is that we have created a world where the petroleum industry is more powerful than any person, idea, government, or country. And so is the banking industry, and the tech industry, and the pharmaceutical industry, and the prison industry, and the war industry.

And all of these industries share one goal, to the exclusion of all others: profit.

Which means that most of the major societal changes happening on the planet are determined not by data, or democracy, or cute social media campaigns, or the pursuit of the greater good; but by the pursuit of profit, for each company, in each quarter.

And these companies and industries are so committed to that narrow goal - hogtied to it, really - that they are willing to hijack elections and start wars and crash the global ecosystem to pursue it. And all of us who share the planet with them - the humans, and the animals, and the oceans - are at the mercy of that pursuit.

The shorthand for this problem is “late-stage capitalism”.

When we are thinking on the global scale - which, again, is the only scale where we can have a measurable effect on the global phenomena of oceans and atmosphere - it becomes clear that the only way to tackle climate change at this point (having failed to do jackshit so far) is to fundamentally change the way the world works.

We need a phase transition.

But you don’t have to take it from me; take it from this team of independent scientists in their report to the U.N.

WE ARE ALL IN THIS TERRIFYING THING TOGETHER

If you’re a person who thought buying organic was a political act, I apologize. You’ve been duped. But it’s not your fault! The idea that our personal consumer choices have an impact on the global economy is not an accident. It is, in fact, a feature of capitalism.

It is good for capitalism when we believe that our personal choices are political choices, because it keeps us from focusing on large-scale problems and organizing to solve them (which, at this point in history, cannot be good for capitalism). Consumer-level environmentalism creates lots of new markets, while having no negative impact whatsoever on the industries that actually run the planet and profit off of its devastation.

If we want to start making political choices, we need to stop thinking of ourselves as heroic individuals, able to single-handedly stop climate change by buying a different phone case. We are part of the world, which is a small place, entirely and inseparably interconnected, and has one very big problem, which we can only solve together.

The big problem thrives when we believe that we are separate people facing separate problems. It thrives when we worry about ourselves, and our beliefs, and what kind of water bottle to buy. It thrives by keeping us distracted, divided, and self-interested.

The truth is, banning straws will not solve our problem, because our problem is bigger than straws. It’s bigger than plastic, and styrofoam, and carbon emissions. It’s bigger than AK-47s and abortion bans. Impeaching Trump won’t solve it, because our problem is bigger than Trump; in fact, our problem is even bigger than “men”.

There is only one man, his name is capitalism, and he’s got us all by the pussy.

SOME COOL DATA ABOUT SOCIALISM

I am a socialist, which means I think we ought to organize our societies around some motives other than profit. I don’t buy that the profit motive is particularly sacred or efficient (except at making profit - it’s very efficient at that), and I prefer almost all the other motives: creativity, kindness, lust, humor, fun.

I dream of a highly democratic post-capitalist society wherein politically-invested citizens make collective, data-driven decisions about how to allocate the resources of this one small planet that we share.

Before we get to the data, a few clarifying points:

- I have scoured the internet for months, and I’ve finally found the best and most succinct summary of the difference between capitalism and socialism. Thank you, comrade Teen Vogue.

- If you’re an American, you might’ve inadvertently ingested a bit of data-averse anti-communist propaganda in your lifetime. Just to check, read this fascinating and brief history of U.S. anti-communism (which, somehow, doesn’t even mention COINTELPRO).

- And finally: no, the Nazis were not socialists.

“Socialism has never worked.”

- According to the World Wildlife Fund, there is only one country in the world which is currently “sustainable” in terms of both human development and environmental footprint: Cuba.

- Here is a comprehensive comparison of health outcomes for socialist vs. capitalist countries, using data from the 1970s and 80s. It finds that Cuba made significantly more gains than its neighbors in all available health indicators (life expectancy, literacy, infant mortality and employment), as did China (as compared to India) and the Soviet Union (as compared to West Germany and Austria). Cuba currently has the lowest infant mortality rate in history and one of the highest literacy rates in the world.

- All of this is to say that “has never worked” is the kind of blanket statement that is designed to shut down conversations. In my opinion, there is a more productive conversation to be had by asking questions such as “in what ways has socialism worked and not worked? What about capitalism?”

“Authoritarianism! Gulags! Freedom!”

- The United States (a capitalist democracy) currently has the highest incarceration rate in the world, with starkly disproportionate incarceration of black Americans. Currently, about 80% of U.S. prisoners are incarcerated for nonviolent crimes, and 22% of U.S. prisoners are awaiting trial (they have not been convicted or sentenced).

- Israel is a capitalist democracy and a close ally of the U.S. In May, Israeli forces murdered 16 peaceful protesters and wounded 65, including children and paramedics. Exactly one year before, they killed 65 peaceful protesters and wounded 2,400. (For the record, I am a Jew, and there is nothing anti-Semitic about acknowledging the fact that Israel is currently engaged in a number of human rights violations.)

- Then, of course, there’s slavery, the holocaust, the Trail of Tears, The Troubles, the Tuskegee Experiments, and compulsory sterilization, to name just a few. All of these acts of violence were carried out within capitalist societies, under the direction of capitalist governments. Is it possible that we are biased against the failures of socialism not because they are worse than those of capitalism, but because capitalism is the dominant paradigm? Is it possible we are experiencing just a touch of Stockholm Syndrome?

“Innovation! Entrepreneurship! Freedom!”

- Cuba just invented the world’s first cancer vaccine, without a speck of venture capital. Actually, public (government) funding gave us most of the vaccines we use today (unless we are Jessica Biel); along with the internet, most of our aviation and space technology, the cameras and touch-screens on our phones, and even Google and Tesla.

- About 30% of research worldwide is currently funded by public money (mostly government grants). Private money is not inherently more “innovative” than public money; the thing that spurs innovation is access to money, period.

- And of course, there is the dark side of privately-funded innovation: the rising cost of insulin, the $750 pill, the possibility that a single company may one day own the entire food chain, and the likelihood that when it comes to research, there is a relationship between funding source and conclusion.

“But people are lazy! And there’s not enough food! And Soviet bloc housing is ugly!”

- It doesn’t matter if people are lazy, we have robots. An Oxford study recently found that 47% of U.S. jobs (and around 13% of jobs worldwide) may be “lost to automation” over the next two decades. And many of our jobs are already bullshit: polls have found that 37% of full-time workers in the UK and 25% in the US are “quite sure that their job makes no meaningful contribution to the world”. Let’s step back a moment and consider the phase “lost to automation”; why is this a “loss” at all? Why aren’t we thanking the robots for allowing 47% of Americans to go ahead and be lazy? (The answer, my friends, is capitalism.)

- We have more than enough food. Hunger is caused by inequality, not scarcity.

- Speaking of inequality, I believe this line of panic stems from a gross misperception about just how much wealth the world has already stockpiled. The U.S. (for example) has quite a lot more money than Russia did in 1917; if we divided all the wealth evenly, each American household would have $760,000. That’s not to say we should do exactly that, it’s just to illustrate that this number is enough to provide quite a high standard of living for everyone - way higher than most of us are currently accustomed to. If the U.S. were to transition to socialism, there is no reason we couldn’t live in style with free healthcare, gorgeous homes, and delicious petri-dish meat.

So what is the actual objection, here?

REVOLUTION: A PRACTICAL, DATA-DRIVEN POLICY IDEA

What all this data says to me is that capitalism has outlived its usefulness. More than 3 billion people on this planet already live in poverty; tens of thousands of children are dying each day from hunger and preventable diseases; we are currently seeing a global refugee crisis of unprecedented proportions, and it’s likely that 1 billion more people will soon be displaced by climate change.

The only political idea I’ve come across that will allow us to respond to so many crises of such magnitude is to stop doing capitalism. And I believe that a massive, strategic, well-organized movement of many millions of people can make that phase transition happen.

I know it seems impossible. But in the words of my late hero, Ursula K. Le Guin:

“We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.”

Our only hope, at this late date, is to pour all our water into one pot. That’s what “organizing” is; that’s what Gandhi and Martin Luther King and Fred Hampton were doing, and that’s what we all need to start doing. I don’t think this blog post will launch a revolution (sorry, trolls), but I think it was worth writing, because it’s my opinion that American liberals - a huge voting bloc with a ton of money - will be considerably more useful to the revolution if we stop wasting our breath, time and political energy on straws.

If you agree, go make friends with your local socialists (I recommend PSL). Give them your folding money to spend on organizing, instead of blowing it at Whole Foods (so Whole Foods can turn around and spend it on union busting). Commit to educating yourself and others about how capitalism works, what it’s done so far, and what the alternatives are.

All of these activities will have more political impact than going vegan, AND you get to eat bacon.

Resources and suggested readings:

The Shock Doctrine by Naomi Klein

Why Socialism? by Albert Einstein

Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism by Kristen Ghodsee

The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin (if you prefer fiction)

Sorry to Bother You (if you prefer movies)

……..

If you love this post (and my other creations), subscribe to me on Patreon.